By Stuart F. Andrews

I went to see Roar the other night at The Royal Cinema in Toronto which essentially means I sat staring at the screen for 102 minutes in disbelief, wracking my brains trying to figure out what the hell could have possessed anyone to make such a film (or how they pulled it off once they decided they were going to!)

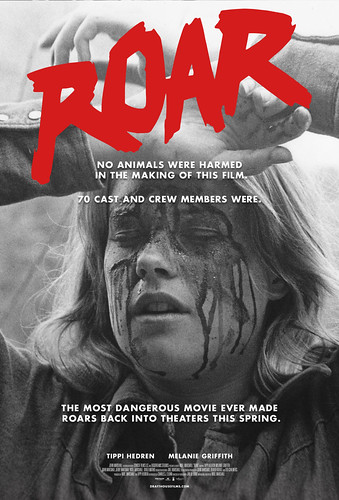

For those who haven’t heard of it, this previously obscure curiosity piece from the early 80’s has been resurrected by Drafthouse Films and is currently doing theatrical dates in Canada and the U.S.

If you haven’t seen the trailer, before we proceed, you’d best be feasting your eyes on this:

Mental, yes! But those feline attacks aren’t just scattered throughout for occasional sprinklings of insanity, the entire movie is jam-packed with wall to wall ‘animal on human’ molestations.

It’s the only film Noel Marshall (Executive Producer on The Exorcist) ever directed, a passion project that took eleven years to complete. Shot largely on his ranch in California with a few scenes filmed in Africa, the production was besieged by accidents, financial setbacks and the logistics of constantly replacing the crew who’d wisely abandon the shoot after a few days of filming. Variety called it the “most disaster-plagued film in the history of Hollywood!” It was an epic flop when it was first released which perhaps explains why it was the only movie Marshall ever directed. Sadly, he passed away a few years ago and never got to see his wild-life ‘disasterpiece’ finally get the attention it deserves.

While the concept of the movie may be difficult to digest, the plot is simple enough: Marshall himself stars as Hank, an animal rights maniac who runs a wild-life reserve in Kenya for large cats, but not only species indigenous to Africa, almost every variety of big felines from around the world can be found here – lions, tigers, cheetahs, leopards, panthers, cougars and even little liger cubs (lion-tiger cross-breeds). I’m not sure a reasonable explanation is ever offered for why so many diverse species are grouped together but that’s just one of the many ways in which this film is deeply confused.

Not only do the animals live on the reserve, they live in Hank’s cabin too. His living room is filled with a pride of full-grown lions who smother him whenever he tries to get through the front door. When he’s not receiving non-stop maulings at home, he’s out fighting a gang of evil game hunters intent on wiping out his collection of exotic creatures (you can easily tell the hunters are evil because their leader is a swarthy bloke with a thick Spanish accent.)

Hank’s off on one such adventure the day his wife (played by real wife and fellow animal lover Tippi Hedren) and children (played by step-daughter Melanie Griffith and sons John and Jerry Marshall) arrive in Kenya for a visit. You can tell from their preponderance of white skin and blonde hair that these are the good guys. Having no idea what they’re getting into, they enter his cabin only to be tormented, persecuted and harangued by every manner of large cat you can imagine for most of the film’s running time. Supposedly, Marshall cast his own family because it would’ve been irresponsible to put real actors in such dangerous situations. Thank God he was being responsible!

In a nod to her most famous role, the first creature to harass Ms. Hedren is a tropical bird. But as gruelling as working for Mr. Hitchcock must have been, surely it was nothing compared to what she was subjected to in Roar.

It’s hard to describe what happens next or to even fathom why it’s happening next but essentially what happens next is a bumbling, slapstick, creature comedy cranked up to harrowing degrees of high anxiety. Due to the unpredictable nature of the animals in the cast, Roar plays like a weird mix of Born Free, The Great Outdoors, Swiss Family Robinson and Night of the Living Dead, except with flesh-eating lions instead of flesh-eating ghouls. Plus, it’s the only film I’ve ever seen where the animals share an on-screen directing credit with the filmmaker!

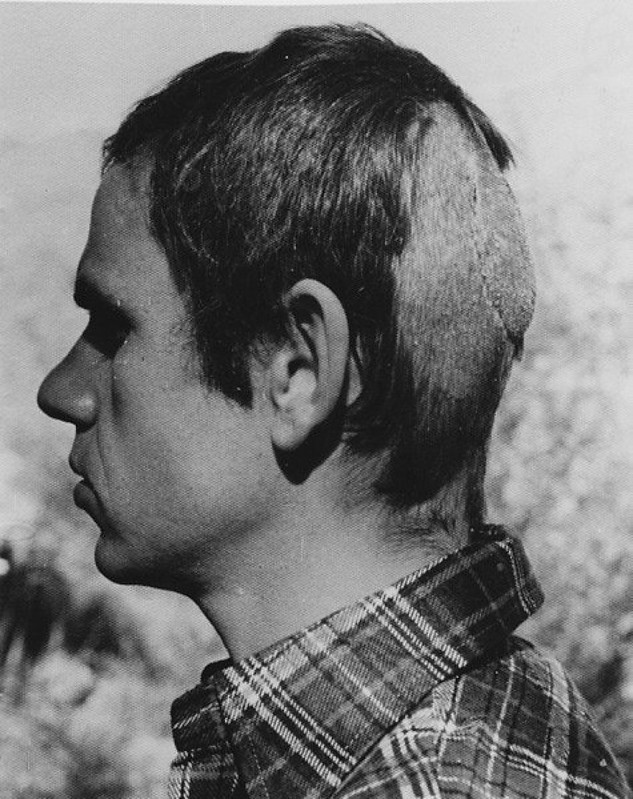

Supposedly, 70 people were injured making the movie. No surprises there. Throw a film crew in the middle of 100 great cats running wild and it’s amazing 70 people weren’t eaten! Marshall himself contracted gangrene from multiple wounds, Hedren sustained a broken leg and not for the first time obviously but Melanie Griffith had to have facial reconstructive surgery (her mauling survives intact in the film). However, it was cinematographer Jan de Bont who sustained one of the worst injuries of anyone involved. He was scalped by a lion and required 220 stitches to sew his head back together.

When he wasn’t bleeding to near death, Mr. de Bont did a fantastic job capturing the insanity that ensued, utilizing cleverly placed camera setups with lots of coverage. The montage is likewise a technical marvel with about a dozen editors credited for dynamically piecing the madness together without ever spatially confusing the audience. Roar is an impressive bit of craftsmanship all round but that doesn’t explain why the hell it ever got made!

Presumably, Marshall and Hedren were trying to draw attention to not only how gorgeous these animals are (and they do indeed capture the majestic beauty of these cats in the brief glimpses we see of them not munching on human beings) but also to protest the brutal travesties of big game hunting. But as environmentalists go, Marshall and company were more than a little bewildered. If you haven’t seen the film, you may want to stop reading now because it’s impossible to discuss the philosophical absurdities of Roar without revealing the ending.

Following the endless chase sequences in the cabin, Hank returns to teach his family that big cats are but misunderstood creatures that when you get to know better, are actually loveable critters who just want to be snuggled and cuddled by their human friends. Essentially, Marshall reduces these ferocious predators to little more than over-sized, stuffed animals.

There’s an autobiographical element here though because Marshall, Hedren and Griffith lived with a full-grown male lion named Neil in their own house and kept a collection of 100 great cats on a ranch north of Los Angeles where the majority of Roar was filmed.

The problem here obviously is that jungle cats aren’t teddy bears. Just ask Jan de Bont! Marshall is guilty of anthropomorphizing them to an absurd degree. Plus, there’s something distastefully grandiose about daring to live in the same house with a full-grown male lion. Like Tony Montana and his tiger, Marshall’s pet reflects a monster sized ego as much as anything to do with animal rights.

In this respect, Roar is a bit like Grizzly Man on glue! And we may very well apply a sentiment that was eloquently expressed in Herzog’s doc. With respects to the creatures Timothy Treadwell foolishly thought he could live amongst, a native scientist remarked, “My people have been living nicely with bears for thousands of years and we know enough to stay out of each other’s way.”

So while Marshall’s heart may have been in the right place, his brains were definitely up his arse. Yes, the great cats are magnificent and no doubt you can form strong bonds with them but they’re far too dangerous to get intimately entangled with. Not acknowledging this reality belies a certain lack of respect for both common sense and the animals in question. In the years since the movie was made, Tippi Hedren has expressed regret and embarrassment for allowing Neil to live in the same home as her 14 year old daughter, Melanie.

But all eco-confusion aside, Roar is a unique bit of cinema that if possible, should be experienced on the big screen with a room full of equally astonished spectators. Initially, I was cautious about it because I’ve grown weary of films being offered to audiences for the purposes of ridicule, presented for seemingly no other purpose than to allow viewers an opportunity to feel superior to the work onscreen. As bonkers as something like The Room may be, seeing it with an aggressively contemptuous audience is a wretched experience.

Thankfully, that’s not the case here. This isn’t a film that invites derision. It’s too well crafted and inspired to be easily dismissed. But as all of its insanity can be traced back to a deep rooted misconception about human and animal relationships, it’s guaranteed to confound the senses in the most pleasurable ways possible. In a culture of filmmaking increasingly dominated by big budget, market-researched titles cobbled together with pre-fabricated predictability, to experience the wild and unpredictable thrills of Roar on the big screen makes for a refreshing and fascinating encounter.

Perhaps the time has come for humans to step aside and let the lions and tigers direct for a bit?

Discuss this article on The Mortuary or Chonebook.